My unedited org-noter notes from the classic book “Fluent Python – Clear, Concise, and Effective Programming” by Luciano Ramalho.

The notes for this are messy, sorry about that. There are some chapters I could not get time to finish so they are left as TODOs for now.

Outline and Notes

Each chapter’s summary page is really useful. We should always start with the summary if we were to review these topics in the future, having already read them at least once before.

The things that are useful and I want to create a habit for, I write a coment with the word: “TO_HABIT” so that we can search it easily.

Part I. Data Structures

Chapter 1. The Python Data Model

Seeing python as a “framework”

This gives us some use cases / purpose for implementing special methods to interface w python as a “framework”

the special methods are dunder methods

We implement special methods when we want our objects to support and interact with fundamental language constructs such as: • Collections • Attribute access • Iteration (including asynchronous iteration using async for) • Operator overloading • Function and method invocation • String representation and formatting • Asynchronous programming using await • Object creation and destruction • Managed contexts using the with or async with statements

What’s New in This Chapter

A Pythonic Card Deck

this is a demonstrative example on how we can adapt to the “interface” for the “framework” that is python.

Class Composition and how Delegation pattern in the data model helps

our getitem delegates to the [] operator of self._cards, our deck automatically supports slicing. Here’s

- The use of base classes allows OOP benefits for us such as being able to delegate functionality.

- Delegation is different from forwarding

- this python example is closer to the concept of “forwarding” actually

| |

How Special Methods Are Used

- NOTE: built-ins that are variable sized under the hood have an

ob_sizeattribute that holds the size of that collection. This makes it faster to calllen(my_object)since it’s not really a function call, the interpreter just reads off the pointer.

- Emulating Numeric Types

- it’s all about implementing the number-class related dunder methods, then anything can behave like a number

- String Representation

__repr__

- repr is different from string in the sense that it’s supposed to be a visual representation of the creation of that object. Therefore, it should be unambiguous, and if possible, match source code necessary to recreate the represented object

- repr is not really for display purposes, that’s what

strbuiltin is for - implement the special function

reprfirst thenstr

- String Representation

- Boolean Value of a Custom Type

default: forward to bool() elif len()

By default, instances of user-defined classes are considered truthy, unless either bool or len is implemented. Basically, bool(x) calls x._bool_() and uses the result. If bool is not implemented, Python tries to invoke x._len_(), and if that returns zero, bool returns False. Otherwise bool returns True.

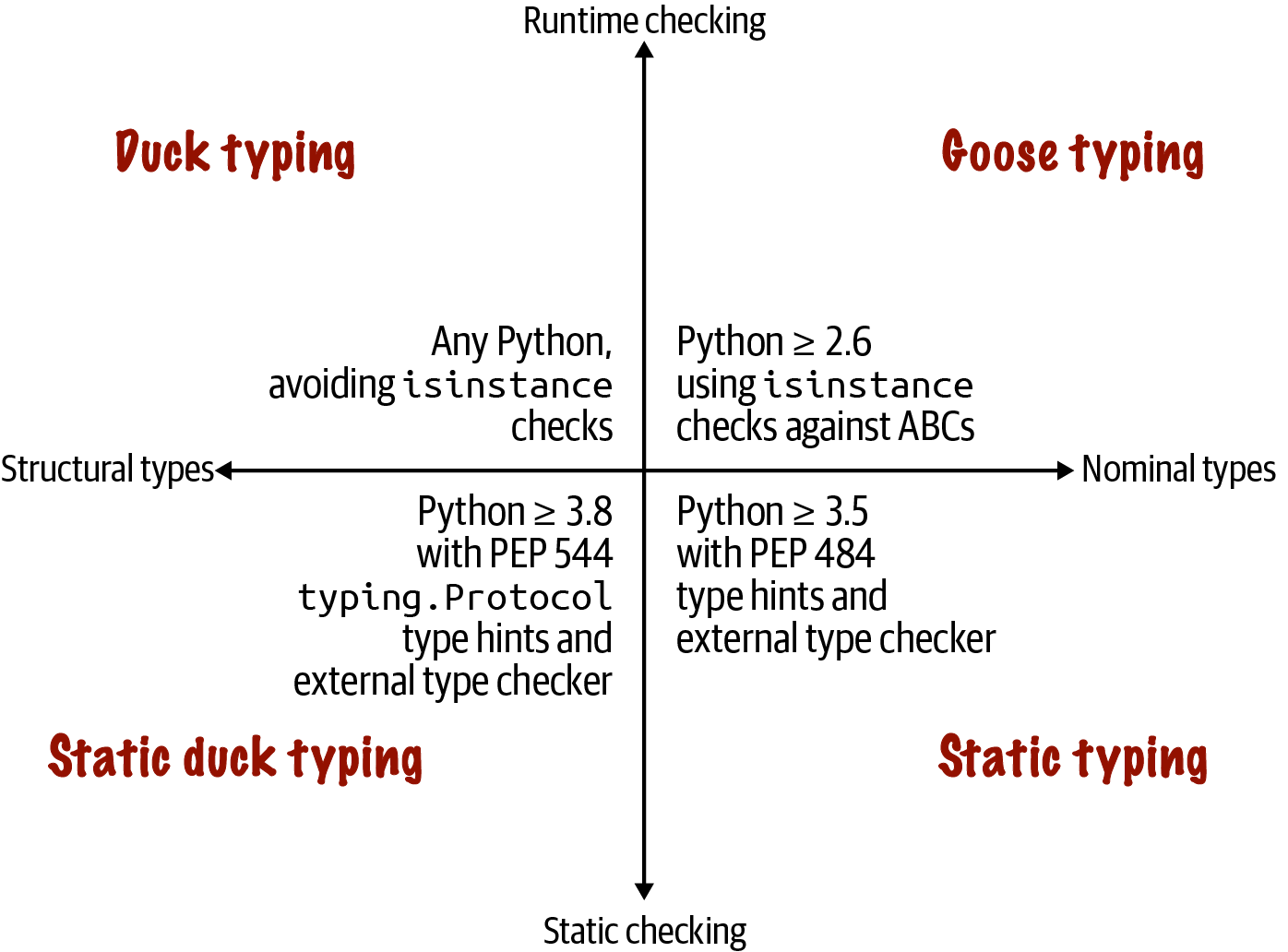

- Collection API

The collections api is new, and it unifies the 3 following interfaces: • Iterable to support for, unpacking, and other forms of iteration • Sized to support the

lenbuilt-in function • Container to support theinoperatorThere’s no need to inherit from these ABCs specifically, as long as the dunder methods are implemented then it’s considered as satisfying the ABC

Specialisations of Collection

Three very important specializations of Collection are: • Sequence, formalizing the interface of built-ins like list and str • Mapping, implemented by dict, collections.defaultdict, etc. • Set, the interface of the set and frozenset built-in types

I want to use the vocabulary here when describing what primitives I want to use.

python dicts are “ordered” in the sense that the insertion order is preserved

- there’s nothing else we can do about the ordering property (e.g. manipulating[rearranging] the order and such)

Overview of Special Methods

- there’s a bunch, the latest ones are more on the async support side, they will be covered throughout the book

Why len Is Not a Method

“Practicality beats purity”.

- there’s no method call for

len(x)when x is a CPython built-in because it’s a direct read of a C-struct - for custom objects, we can implement the dunder method

__len__ - it kinda looks like a functional style (since len is a fn) in a OOP-styled language. To reconcile this, we can think of

absandlenas unary functions!

Chapter Summary

Further Reading

Python’s DataModel can be seen as a MetaObject Protocol

Metaobjects The Art of the Metaobject Protocol (AMOP) is my favorite computer book title. But I mention it because the term metaobject protocol is useful to think about the Python Data Model and similar features in other languages. The metaobject part refers to the objects that are the building blocks of the language itself. In this context, protocol is a synonym of interface. So a metaobject protocol is a fancy synonym for object model: an API for core language constructs.

Chapter 2. An Array of Sequences

What’s New in This Chapter

Overview of Built-in Sequences

- two factors to group sequences by:

- by container (heterogeneous) / flat (homogeneous) sequences

- Container sequences: can be heterogeneous

- holds references (“pointers”)

- Flat sequences: are homogeneous

- holds values

- Container sequences: can be heterogeneous

- by mutability / immutability

- by container (heterogeneous) / flat (homogeneous) sequences

- things like generators can be seen in the context of sequences themselves “To fill up sequences of any type”

Mem Representation for Python Objects: have a header (with metadata) and value

example of meta fields (using float as a reference):

- refcount

- type

- value

Every Python object in memory has a header with metadata. The simplest Python object, a float, has a value field and two metadata fields: • ob_refcnt: the object’s reference count • ob_type: a pointer to the object’s type • ob_fval: a C double holding the value of the float On a 64-bit Python build, each of those fields takes 8 bytes. That’s why an array of floats is much more compact than a tuple of floats: the array is a single object holding the raw values of the floats, while the tuple consists of several objects—the tuple itself and each float object contained in it.

List Comprehensions and Generator Expressions

List Comprehensions and Readability

- a loop has generic purpose, but a listcomp’s purpose is always singular: to build a list

- we should stick to this purpose and not introduce abuse mechanisms like adding in side-effects from listcomp evaluations

- List comprehensions build lists from sequences or any other iterable type by filtering and transforming items.

Scope: listcomps have a local scope, use walrus operator to expand the scope to its outer frame

``Local Scope Within Comprehensions and Generator Expressions''

if that name is modified using global or nonlocal, then the scope is accordingly set

defines the scope of the target of := as the enclos‐ ing function, unless there is a global or nonlocal declaration for that target.

- Listcomps Versus map and filter

Cartesian Products

This is the part where we have more than one iterable within the listcomp

- Generator Expressions

Tuples Are Not Just Immutable Lists

The immutable list part is definitely one of the main features.

It should also be seen as a nameless record.

Tuples as Records

- some examples of tuple unpacking:

- the loop constructs automatically support unpacking, we can assign vars even for each iteration of the loop

- the

%formatting operator will also unpack values within the tuple when doing string formats

- some examples of tuple unpacking:

Tuples as Immutable Lists

2 benefits:

- clarity: the length of tuple is fixed thanks to its immutability

- performance: memory use is a little better, also allows for some optimisations

Warning: the immutability is w.r.t references contained within the tuple, not values

So tuples containing mutable items can be a source of bugs Also, unhashable tuple => can’t be inserted as a dict key or set

Tuple’s Performance Efficiency Reasons

Tuples are more efficient because:

- bytecode: tuple has simpler bytecode required: Python compiler generates bytecode for a tuple constant in one operation; but for a list literal, the generated bytecode pushes each element as a separate constant to the data stack, and then builds the list.

- constructor:

tuple construction from existing doesn’t need any copying, it’s the same reference:

- the list constructor returns a copy of a given list if its

list(l) - tuple constructor returns a reference to the same

tif we dotuple(t)(because they’re immutable anyway so why not same reference)

- the list constructor returns a copy of a given list if its

- amortisation: tuple, since fixed size, doesn’t need to account for future size changes by amortising that operation

- no extra layer of indirection The references to the items in a tuple are stored in an array in the tuple struct,while a list holds a pointer to an array of references stored elsewhere. The indirection is necessary because when a list grows beyond the space currently allocated, Python needs to reallocate the array of references to make room. The extra indirection makes CPU caches less effective.

- Comparing Tuple and List Methods

Unpacking Sequences and Iterables

- safer extraction of elements from sequences

- works with any iterable object as the datasource, including iterators.

- for the iterable case, as long as the iterable yields exactly one item per variable in the receiving end (or

*is used to do a glob capture)

- for the iterable case, as long as the iterable yields exactly one item per variable in the receiving end (or

Parallel assignment

This is the multi-name assignments that we do, and how involves sequence unpacking

most visible form of unpacking is parallel assignment; that is, assigning items from an iterable to a tuple of variables, as you can see in this example: >>> lax_coordinates = (33.9425, -118.408056) >>> latitude, longitude = lax_coordinates # unpacking >>> latitude

Using * to Grab Excess Items

- classic case is the use of the grabbing part for varargs

- context of parallel assignment, the

*prefix can be applied to exactly one variable, but it can appear in any position

Unpacking with * in Function Calls and Sequence Literals

- the use of the unpacking operator is context-dependent, so in the context of function calls and the creation of sequences, they can be used multiple times. In the context of parallel asisgnment, it’s a singular use (else there’s going to be ambiguity on how to partition values in the sequence)

- Nested Unpacking

GOTCHA: single-item tuple syntax may have silent bugs if used improperly

Both of these could be written with tuples, but don’t forget the syntax quirk that single-item tuples must be written with a trailing comma. So the first target would be (record,) and the second ((field,),). In both cases you get a silent bug if you forget a comma.

Pattern Matching with Sequences

Pattern matching is an example of declarative programming: the code describes “what” you want to match, instead of “how” to match it. The shape of the code follows the shape of the data, as Table 2-2 illustrates.

- here’s the OG writeup for structural pattern matching. Some points from it:

- Therefore, an important exception is that patterns don’t match iterators. Also, to prevent a common mistake, sequence patterns don’t match strings.

- the matching primitives allow us to use guards on the match conditions (see here)

- there’s support for defining sub-patterns like so:

1case (Point(x1, y1), Point(x2, y2) as p2): ...

- here’s a more comprehensive tutorial PEP 636 - Structural Pattern Matching

Pattern-matching is declarative

Pattern matching is an example of declarative programming: the code describes “what” you want to match, instead of “how” to match it. The shape of the code fol‐ lows the shape of the data, as Table 2-2 illustrates.

python’s

matchgoes beyond just being aswitchstatement because it supports destructuring similar to elixir- random thought: this features is really useful if we were to write out a toy interpreter for some source code. Here’s lis.py

On the surface, match/case may look like the switch/case statement from the C lan‐ guage—but that’s only half the story.4 One key improvement of match over switch is destructuring—a more advanced form of unpacking. Destructuring is a new word in the Python vocabulary, but it is commonly used in the documentation of languages that support pattern matching—like Scala and Elixir. As a first example of destructuring, Example 2-10 shows part of Example 2-8 rewrit‐ ten with match/case.

class-patterns gift us the ability to do runtime type checks

1case [str(name), _, _, (float(lat), float(lon))]:the constructor-like syntax is not a constructor, it’s a runtime check

the names (

name,lat,lon) are binded here and are available for referencing thereafter within the codeblockthis is really interesting, it’s in the context of patterns that the syntax does runtime type checking and the code does

The expressions str(name) and float(lat) look like constructor calls, which we’d use to convert name and lat to str and float. But in the context of a pattern, that syntax performs a runtime type check: the preceding pattern will match a four-item sequence in which item 0 must be a str, and item 3 must be a pair of floats. Additionally, the str in item 0 will be bound to the name variable, and the floats in item 3 will be bound to lat and lon, respectively. So, although str(name) borrows the syntax of a constructor call, the semantics are completely different in the context of a pattern. Using arbitrary classes in patterns is covered in “Pattern Matching Class Instances” on page 192.

Pattern Matching Sequences in an Interpreter

it’s interesting how the python 2 code was described as “a fan of pattern matching” because it matches on the first element and then the tree of control flow paths does their job, so it’s really like a switch

this switch-like pattern-matching style is something abstract even more so than in it’s concrete programming language implementation that we have been discussing so far

the catch-all is used for error-handling purposes here. In general there should always be a fallthrough case instead of going for no-ops which will end up being more silent

Slicing

Why Slices and Ranges Exclude the Last Item

this refers to the fact that one end of the range is closed (inclusive) and the other is open (exclusive).

- easy to calculate lengths

- easy to split / partition without creating overlaps

Slice Objects

- useful to know this because it lets you assign names to slices, like spreadsheets allow the naming of cell-ranges

Multidimensional Slicing and Ellipsis

This is more useful in the context of numpy lib, the book doens’t include examples here for the python stdlib

- built-ins are single dim, except for memoryview Except for memoryview, the built-in sequence types in Python are one-dimensional, so they support only one index or slice, and not a tuple of them.

- Multiple indexes or slices get passed in as tuples

a[i,j]is evaluated asa.__getitem__((i,j))e.g. numpy multi-dim array accesses ellipsisclass is a singleton, the sole object beingElipsis- a similar case is

boolclass andTrue,False

- a similar case is

- so in numpy, if x is a four-dimensional array,

x[i, ...]is a shortcut forx[i, :, :, :,]

Assigning to Slices

Applies to mutable sequences.

Gotcha: when LHS of assignment is slice, the RHS must be iterable

In the example below, we’re trying to graft some sequence to another. With that intent, we can only graft an iterable onto another sequence, not a single element. Hence, the requirement that the RHS must be iterable.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12l = list(range(10)) try: # so this is wrong: l[2:5] = 100 except: print("this will throw an error, we aren't passing in an iterable for the grafting.") finally: # and this is right l[2:5] = [100] print(l)

Using + and * with Sequences

- both

+and-create new objects without modding their operands

Building Lists of Lists

Gotcha: Pitfall of references to mutable objects – using

a * nwhere a contains sequence of mutable items can be problematicActually applies to other mutable sequences as well, in this case it’s just a list that we’re using

Just be careful what the contained element’s properties are like.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11my_mutable_elem = ['apple', 'banana'] print(f"my mutable elem ref: {id(my_mutable_elem)}") list_of_lists = [ my_mutable_elem ] * 2 print(f"This creates 2 repeats \n{list_of_lists}") print(f"(first ref, second ref) = {[id(elem) for elem in list_of_lists]}") list_of_lists[0][0] = 'strawberry' print(f"This mods all 2 repeated refs \n{list_of_lists}") print(f"(first ref, second ref) = {[id(elem) for elem in list_of_lists]}")Here’s the same gotcha using tic-tac-toe as an example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20good_board = [['_'] * 3 for i in range(3)] bad_board = [['_'] * 3] * 3 print(f"BEFORE, the boards look like this:\n\ \tGOOD Board:\n\ \t{ [row for row in good_board] }\n\ \tBAD Board:\n\ \t{ [row for row in bad_board] }\n") # now we make a mark on the boards: good_board[1][2] = 'X' bad_board[1][2] = 'X' print(f"AFTER, the boards look like this:\n\ \tGOOD Board:\n\ \t{ [row for row in good_board] }\n\ \tBAD Board:\n\ \t{ [row for row in bad_board] }\n")

Augmented Assignment with Sequences

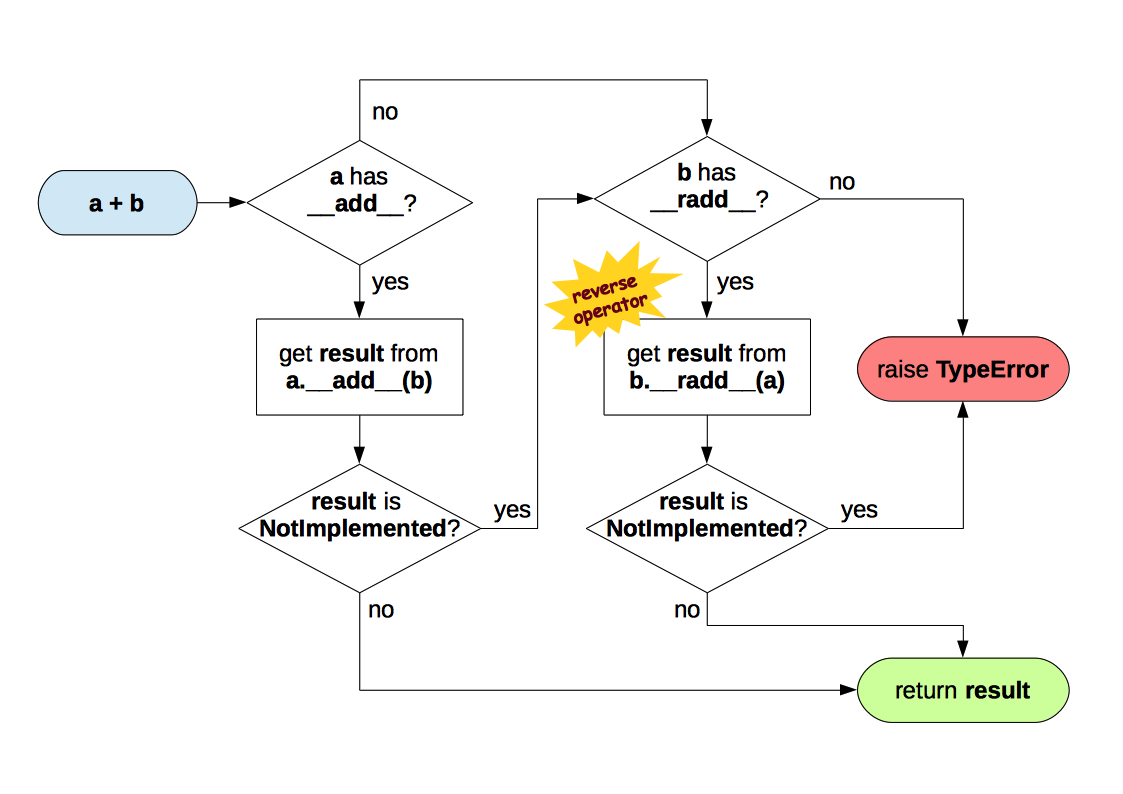

This refers to the in-place versions of the sequence operators. in ==, there are 2 cases:

Case A: Identity of

achanges- the dunder method

__iadd__was not available for use - so

a + bhad to be evaluated and stored as a new id - and that id was then referenced by

aas part of the new assignment

- the dunder method

Case B: Identity of

adoes not change- this would mean that

ais actually mutated in-place - it would have used the dunder method

__iadd__

- this would mean that

In other words, the identity of the object bound to a may or may not change, depending on the availability of

__iadd__.In general, for mutable sequences, it is a good bet that

__iadd__is implemented and that += happensdoing += for repeated concats of immutable sequences is inefficient

however, str contacts have been optimised in CPython, it’s alright to do that in CPython. Extra space would have been allocated to amortise the new space allocations.

A += Assignment Puzzler

Learnings!

I take three lessons from this:

• Avoid putting mutable items in tuples.

• Augmented assignment is not an atomic operation—we just saw it throwing an exception after doing part of its job.

• Inspecting Python bytecode is not too difficult, and can be helpful to see what is going on under the hood.

Example

it’s a peculiarity in the += operator!

Learnings:

I take three lessons from this:

• Avoid putting mutable items in tuples.

• Augmented assignment is not an atomic operation—we just saw it throwing an exception after doing part of its job.

• Inspecting Python bytecode is not too difficult, and can be helpful to see what is going on under the hood.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17t = (1,2, [30, 40]) print(t) try: t[2] += [50, 60] except: print("LMAO complaints") finally: print(t) try: t[2].extend([90, 100]) except: print("this won't error out though") finally: print(t)

list.sort Versus the sorted Built-In

in-place functions should return

Noneas a conventionThere’s a drawback to this: we can’t cascade calls to this method

- python’s sorting uses timsort!

Managing Ordered Sequences with bisect (extra ref from textbook)

When a List Is Not the Answer

Arrays: best for containing numbers

- an array of float values does not hold full-fledged float instances, but only the packed bytes representing their machine values—similar to an array of double in the C language.

- examples:

- typecode b => byte => 8 bits over signed and unsigned regions ==> [-128, 127] range of representation

- for special cases of numeric arrays for bin data (e.g. raster images),

bytesandbytearraytypes are more appropriate!

Memory Views

Examples

id vs context

The learning from this is that the

memoryviewobjects and the memory that they provide a view of are two different regions of memory. id vs context.So here, m2, m3 and all have different id references, but the memory region that they give a view of is all the same.

That’s why we can mutate using one memory view and every other view also reflects that change.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32from array import array # just some bytes, the sequence is buffer-protocol-adherent octets = array("B", range(6)) print(octets) # builds a new memoryview from the array m1 = memoryview(octets) print(m1) # exporting of a memory view to a list, this creates a new list (a copy!) print(m1.tolist()) # builds a new memoryview, with 2 rows and 3 columns m2 = m1.cast('B', [2,3]) print(m2) print(m2.tolist()) m3 = m1.cast('B', [3,2]) print(m3) print(m3.tolist()) # overwrite byte m2[1,1] = 22 # overwrite byte m3[1,1] = 33 print(f"original memory has been changed: \n\t{octets} ") print(f"m1 has been changed:\n\t { m1.tolist() }") print(f"m2 has been changed:\n\t { m2.tolist() }") print(f"m3 has been changed:\n\t {m3.tolist()}")

corruption

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35from array import array from sys import byteorder print(byteorder) numbers = array('h', [-2,-1,0,1,2]) memv = memoryview(numbers) print(len(memv)) print(memv[0]) # cast the half as a byte, so the resultant sequence will have double the elements: memv_oct = memv.cast('B') # the numbers are stored in little endian format print(memv_oct.tolist()) # so -2 as a 2-byte signed short will be (little endian binary) 0xfe 0xff (254, 255) # so we get: # -2: 0xfe 0xff (254, 255) # -1: 0xff 0xff (255, 255) # 0: 0x00 0x00 (0, 0) # 1: 0x01 0x00 (1, 0) # 2: 0x02 0x00 (2, 0) # asisgns the value of 4 to byte-offset 5 memv_oct[5] = 4 print( numbers ) # so this change is to the 2nd byte of the third element of numbers # byte index 5 is the high byte (since it's little endian so bytes are low -> high) # so the 3rd element is now [0, 0x0400] # = a + (b*256) = 0 + (4 * 256) is 1024 in decimal # NOTE: Note the change to numbers: a 4 in the most significant byte of a 2-byte unsigned # integer is 1024.

Extra: “Parsing binary records with struct”

Some takeaways:

- Proprietary binary records in the real world are brittle and can be corrupted easily. examples:

- string parsing: paddings, null terminated, size limits?

- endianness problem: what byteorder was used for representing integers and floats (CPU-architecture-dependent)?

- always explore pre-built solutions first instead of building yourself:

- for data exchange,

picklemodule works great, but have to ensure python versions align since the default binary formats may be different. Reading a pickle also may run arbitrary code.

- for data exchange,

- if the binary exchange uses multiple programming languages, standardise the serialisation. Serial forms:

- multi-platform binary serialisation formats:

- JSON

- Proprietary binary records in the real world are brittle and can be corrupted easily. examples:

bot assisted concept mapping

Here’s a bot-assisted concept map between unix

mmapandmemoryviews:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64Memory mapping a file is a powerful technique that allows access to file data as if it were in memory, and the concepts connect naturally between the Unix world (via `mmap` system calls) and Python (via the `mmap` module and `memoryview` objects). **Unix World: mmap** - **Definition:** The Unix `mmap` system call maps files or devices into a process's address space, enabling file I/O by reading and writing memory. This is efficient for large files because data is loaded on demand, and multiple processes can share the same mapped region[1]. - **Usage:** After opening a file, `mmap` associates a region of virtual memory with the file. Reading and writing to this memory behaves as if you were reading and writing to the file itself. The system manages when data is actually read from or written to disk, often using demand paging[1]. - **Types:** Both file-backed (mapping a file) and anonymous (not backed by a file, similar to dynamic allocation) mappings are supported. Shared mappings allow interprocess communication, while private mappings isolate changes to one process[1]. **Python World: mmap Module** - **Definition:** Python’s `mmap` module provides a high-level interface to memory-mapped files, closely mirroring the Unix `mmap` functionality. You must provide a file descriptor (from `fileno()` or `os.open()`) and specify the mapping size and access mode[2][3]. - **Usage:** Memory-mapped file objects behave like both file objects and mutable byte arrays, allowing random access and slicing. You can read and write data by indexing or slicing, and you can seek through the file as if it were a standard file object[2][3]. - **Access Modes:** You can specify read-only, write-through (changes go directly to the file), or copy-on-write (changes are local)[4][5]. **Python World: memoryview** - **Definition:** The `memoryview` object provides a safe way to access the internal data of an object that supports the buffer protocol, such as `bytes`, `bytearray`, or a memory-mapped file object[6]. - **Usage:** With a `memoryview`, you can manipulate large data structures without copying them, which is especially useful for memory-mapped files. It allows you to pass a view of the data to functions or slice it efficiently, avoiding unnecessary memory duplication[6]. - **Connection to mmap:** When you create a memory-mapped file in Python, you can use `memoryview` to work with the data as a buffer, enabling efficient manipulation and sharing of large data sets. **Linking the Concepts** - **Memory Mapping:** Both Unix `mmap` and Python’s `mmap` module allow you to treat file data as if it were in memory, enabling efficient random access and sharing between processes[1][2][3]. - **Efficient Data Access:** Using `memoryview` in Python is analogous to working directly with the mapped memory region in Unix, as both avoid copying large chunks of data and allow efficient manipulation of file contents[6]. - **Interprocess Communication:** In Unix, shared memory mappings (`MAP_SHARED`) allow processes to communicate by reading and writing the same memory region. In Python, you can achieve similar effects by sharing a memory-mapped file object between processes[1][2]. - **Performance:** Both approaches leverage the operating system’s memory management to reduce I/O overhead and enable fast, random access to file data. **Summary Table** | Concept | Unix (`mmap`) | Python (`mmap` module) | Python (`memoryview`) | |------------------------|------------------------------|-----------------------------------|-------------------------------| | Purpose | Map files to memory | Map files to memory | View memory as buffer | | Access Method | System call | Module/object | Object | | Sharing | Shared/private mappings | Shared via file object | View of existing buffer | | Efficiency | Demand paging, no copy | Demand paging, no copy | No copy, efficient slicing | | Use Case | IPC, efficient file I/O | Efficient file I/O, IPC | Efficient data manipulation | By understanding these connections, you can leverage memory mapping for efficient file handling and data sharing across both Unix and Python environments. [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mmap [2] https://docs.python.org/3/library/mmap.html [3] https://github.com/python/cpython/blob/master/Doc/library/mmap.rst [4] https://pymotw.com/3/mmap/ [5] https://realpython.com/python-mmap/ [6] https://smart-spatial.com/data%20science/2017/09/22/MemoryView/ [7] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/63553692/how-to-use-memory-mapped-file-in-python-linux/63554607 [8] https://pymotw.com/3/mmap/index.html [9] https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/712651/does-mmap-allow-creating-a-mapping-that-is-much-larger-than-the-amount-of-physic [10] https://deepaksood619.github.io/computer-science/operating-system/memory-mapping-mmap/ [11] https://www.cmi.ac.in/~madhavan/courses/prog2-2012/docs/python-3.2.1-docs-html/library/mmap.html [12] https://www.blopig.com/blog/2024/08/memory-mapped-files-for-efficient-data-processing/ [13] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/4991533/sharing-memory-between-processes-through-the-use-of-mmap/4991631 [14] https://documentation.help/Python-2.4/module-mmap.html [15] https://docs.python.org/3.4/library/mmap.html?highlight=mmap [16] https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/zos/2.4.0?topic=functions-mmap-map-pages-memory [17] https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/mmap.2.html [18] https://programmingappliedai.substack.com/p/what-is-mmap-in-linux-and-how-it [19] https://w3.cs.jmu.edu/kirkpams/OpenCSF/Books/csf/html/MMap.html [20] https://www.ibm.com/docs/ssw_ibm_i_74/apis/mmap.htm [21] https://www.unix.com/man-page/linux/3/mmap/ [22] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/47437481/python-can-i-get-a-memoryview-or-a-bytearray-mapping-to-a-mmap [23] https://docs.vultr.com/python/built-in/memoryview [24] https://pymotw.com/2/mmap/ [25] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ky1n6luzL3Y

“casting” in memoryview vs Elixir ecto “casting”

The mental models are different.

“casting” with memoryview is about interpreting memory as a different type, not about automatic type conversion or validation as in Elixir changesets. The term is used more loosely in Python, while in Elixir, it is a formal, declarative operation for data preparation.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37The use of the term **"cast"** in the context of Python `memoryview` is not the same as in Elixir changesets, even though both involve types or transformations. **Python `memoryview` and Casting** - **Casting in Python `memoryview`:** When people refer to "casting" with `memoryview`, they usually mean taking a slice of a memoryview or viewing the underlying buffer as a different type (sometimes using modules like `ctypes` or `numpy` to achieve type reinterpretation). However, the built-in `memoryview` object itself does not perform type conversion; it provides a view into the memory buffer of an object that supports the buffer protocol, such as `bytes`, `bytearray`, or a NumPy array[5][6][1]. - **Type Safety:** The `memoryview` object allows you to manipulate the data as if it were a sequence of bytes or another type (if the underlying buffer supports it), but it does not automatically convert the data to a different type. If you want to reinterpret the data as a different type (e.g., casting bytes to an integer array), you typically use additional libraries or manual conversion, not `memoryview` itself[5][1]. - **No Implicit Type Conversion:** The `memoryview` simply provides a window into the existing data, preserving the memory layout and avoiding data copying[6][8]. Any "casting" is more about how you interpret the bytes, not a formal declaration or transformation of types. **Elixir Changesets and Casting** - **Casting in Elixir Changesets:** In Elixir's Ecto changesets, "casting" refers to the explicit declaration of how data (often from a web form or external source) should be converted or validated into a specific type before being inserted into a database. This is a declarative process that ensures data integrity and type safety. - **Type Conversion:** Casting in Elixir changesets involves actual type conversion (e.g., from a string to an integer or date), and is a core part of the data validation and preparation process. **Comparison Table** | Context | Meaning of "Cast" | Type Conversion | Purpose | |------------------------|------------------------------------------|-----------------|--------------------------------| | Python `memoryview` | Viewing/reinterpreting memory as a type | No (manual only)| Efficient data access/manipulation | | Elixir changesets | Declaring/validating/converting types | Yes | Data validation, preparation | **Summary** In Python, "casting" with `memoryview` is about interpreting memory as a different type, not about automatic type conversion or validation as in Elixir changesets. The term is used more loosely in Python, while in Elixir, it is a formal, declarative operation for data preparation[5][6][1]. [1] https://cython.readthedocs.io/en/latest/src/userguide/memoryviews.html [2] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/71028367/how-to-make-a-custom-python-class-to-support-memoryview-conversion [3] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/48136122/how-do-i-cast-a-slice-of-memoryview-into-c-string-unsigned-char [4] https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html [5] https://blog.finxter.com/converting-python-bytes-to-memoryview/ [6] https://realpython.com/ref/builtin-functions/memoryview/ [7] https://www.stratascratch.com/blog/understanding-data-types-in-python-with-examples/ [8] https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/memoryview.html

NumPy

python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) and how releasing it unlocks better parallelisation

it’s a mutex that protects access to python objects and therefore prevents multiple native threads from executing Python bytecode simultaneously within the same process.

It was intended to be a simplification mechanism to make memory handling simpler but that also means having this mutex limits parallelism.

Typical workarounds:

multi-processing, separate processes, each with their own GIL

offload CPU-intensive work to C-extensions or libs that release the GIL

here’s a bot-written outline on it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50The **Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)** is a core mechanism in CPython, the reference implementation of Python, that ensures only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time, even on multi-core processors[2][4][5]. Here’s a detailed overview: ## **What Is the GIL?** - **Definition:** The GIL is a mutex (mutual exclusion lock) that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple native threads from executing Python bytecode simultaneously within the same process[2][4][7]. - **Purpose:** It exists primarily to simplify CPython’s memory management, especially reference counting, which is not thread-safe by default. Without the GIL, concurrent access to Python objects could lead to race conditions and memory corruption[5][7]. ## **How Does the GIL Work?** - **Single Thread Execution:** Only one thread holds the GIL at any moment, meaning only one thread can execute Python code at a time, even if you have multiple threads running[2][4][6]. - **Thread Switching:** The interpreter periodically releases the GIL, allowing other threads to acquire it and execute Python code. This switching happens frequently, but it means that CPU-bound multithreaded Python programs do not benefit from multiple cores for parallel execution of Python code[2][4]. - **Non-Python Code:** Operations that do not require the Python interpreter (such as I/O or some C extensions like NumPy) can release the GIL, allowing other threads to run Python code or the process to use multiple cores for those operations[2][4]. ## **Why Does the GIL Exist?** - **Memory Management:** Simplifies reference counting and garbage collection by ensuring thread safety for Python objects[5][7]. - **C Extensions:** Makes it easier to write and use C extensions by providing a stable, single-threaded environment for their execution[1][3][7]. - **Implementation Simplicity:** Using a single lock is easier to implement and maintain than fine-grained locking for all Python objects[1][7]. ## **Implications of the GIL** - **Limited Parallelism:** The GIL prevents true parallel execution of Python code in multi-threaded programs, making it a bottleneck for CPU-bound tasks[2][4][5]. - **Workarounds:** For parallelism, Python developers often use multiprocessing (which uses separate processes, each with its own GIL) or offload CPU-intensive work to C extensions or libraries that release the GIL[1][4]. - **Performance Impact:** The GIL can degrade performance in multi-threaded, CPU-bound applications. However, for I/O-bound or single-threaded programs, its impact is minimal[2][4][6]. ## **Future of the GIL** - **Potential Removal:** The Python Steering Council has indicated support for PEP 703, which proposes making a version of CPython without the GIL. This could enable true multi-threaded parallelism in Python in the future[3]. - **Challenges:** Removing the GIL is complex due to backward compatibility and the reliance of many extensions on its guarantees[3][2]. ## **Summary Table** | Feature | Description | |------------------------|-----------------------------------------------------------------------------| | Purpose | Protect Python objects, simplify memory management, enable C extensions | | Execution Model | Only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time | | Impact on Parallelism | Limits CPU-bound parallelism in multi-threaded Python code | | Workarounds | Multiprocessing, C extensions, I/O-bound operations | | Future | Potential removal via PEP 703, but challenges remain | The GIL is a key part of Python’s design, balancing simplicity and safety with some limitations for parallel execution[2][4][5]. [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_interpreter_lock [2] https://wiki.python.org/moin/GlobalInterpreterLock [3] https://developer.vonage.com/en/blog/removing-pythons-gil-its-happening [4] https://realpython.com/python-gil/ [5] https://dev.to/adityabhuyan/understanding-pythons-global-interpreter-lock-gil-and-its-impact-on-concurrency-2da6 [6] https://realpython.com/videos/global-interpreter-lock-overview/ [7] https://dev.to/ohdylan/understanding-pythons-global-interpreter-lock-gil-mechanism-benefits-and-limitations-4aha [8] https://www.pubnub.com/blog/understanding-pythons-global-interpreter-lock/NumPy and SciPy are formidable libraries, and are the foundation of other awesome tools such as the Pandas—which implements efficient array types that can hold non‐ numeric data and provides import/export functions for many different formats, like .csv, .xls, SQL dumps, HDF5, etc.—and scikit-learn, currently the most widely used Machine Learning toolset. Most NumPy and SciPy functions are implemented in C or C++, and can leverage all CPU cores because they release Python’s GIL (Global Interpreter Lock). The Dask project supports parallelizing NumPy, Pandas, and scikit-learn processing across clusters of machines. These packages deserve entire books about them.

Deques and Other Queues

issues with list methods

although we can use

listas a stack / queue (by using.append()or.pop()). However, inserting and removing from the head of the list (the 0-idx end) is costly because the entire list must be shifted in memory => this is why just re-purposing lists is not a good idea.

Characteristics:

- when bounded, every mutation will adhere to the deque capacity for sure.

- hidden cost is that removing items from the middle of a deque is not fast

- append and popleft are atomic, so can be used for multi-threaded applications without needing locks:w

alternative queues in stdlib

- asyncio provides async-programming focused queues

Chapter Summary

Further Reading

- “numpy is all about vectorisation” oprations on array elements without explicit loops

More on Flat vs Container Sequences

``Flat Versus Container Sequences''

Chapter 3. Dictionaries and Sets

What’s New in This Chapter

Extra: Internals of sets and dicts internalsextra

This info is found in the fluentpython website. It considers the strengths and limitations of container types (dict, set) and how it’s linked to the use of hash tables.

Running performance tests

the trial example of needle in haystack has beautiful ways of writing it

1 2 3 4found = 0 for n in needles: if n in haystack: found += 1when using sets, because it’s directly related to set theory, we can use a one-liner to count the needles that occur in the haystack by doing an intersection:

1found = len(needles & haystack)This intersection approach is the fastest from the test that the textbook runs.

the worst times are if we use the

list datastructurefor the haystackIf your program does any kind of I/O, the lookup time for keys in dicts or sets is negligible, regardless of the dict or set size (as long as it fits in RAM).

Hashes & Equality

the usual uniform random distribution assumption as the goal to reach for hashing functions, just described in a different way: to be effective as hash table indexes, hash codes should scatter around the index space as much as possible. This means that, ideally, objects that are similar but not equal should have hash codes that differ widely.

- here’s the oficial docs on the hash function

A hashcode for an object usually has less info than the object that the hashcode is for.

- 64-bit CPython hashcodes is a 64-bit number => \(2^{64}\) possible values

- consider an ascii string of 10 characters (and that there are 100 possible values in ascii) => \(100^{10}\) which is bigger than the possible values for the hashcode.

By the way it’s actually salted, there’s some nuances on how the salt is derived but it should be such that each shell has a particular salt.

The modern hash function is the siphash implementation

Hash Implementation

- each row in the table is traditionally a “bucket”. In the case of sets, it’s just a single item that the bucket will hold

- For 64-bit CPython,

- It’s a 64-bit hash code that points to a 64 bit pointer to the element value

- so the table doesn’t need to keep track of indices, offsets work fine since they are fixed-width.

- Also it keeps 1/3 extra space that gets doubled when encroached so there’s some amortisation happening there also.

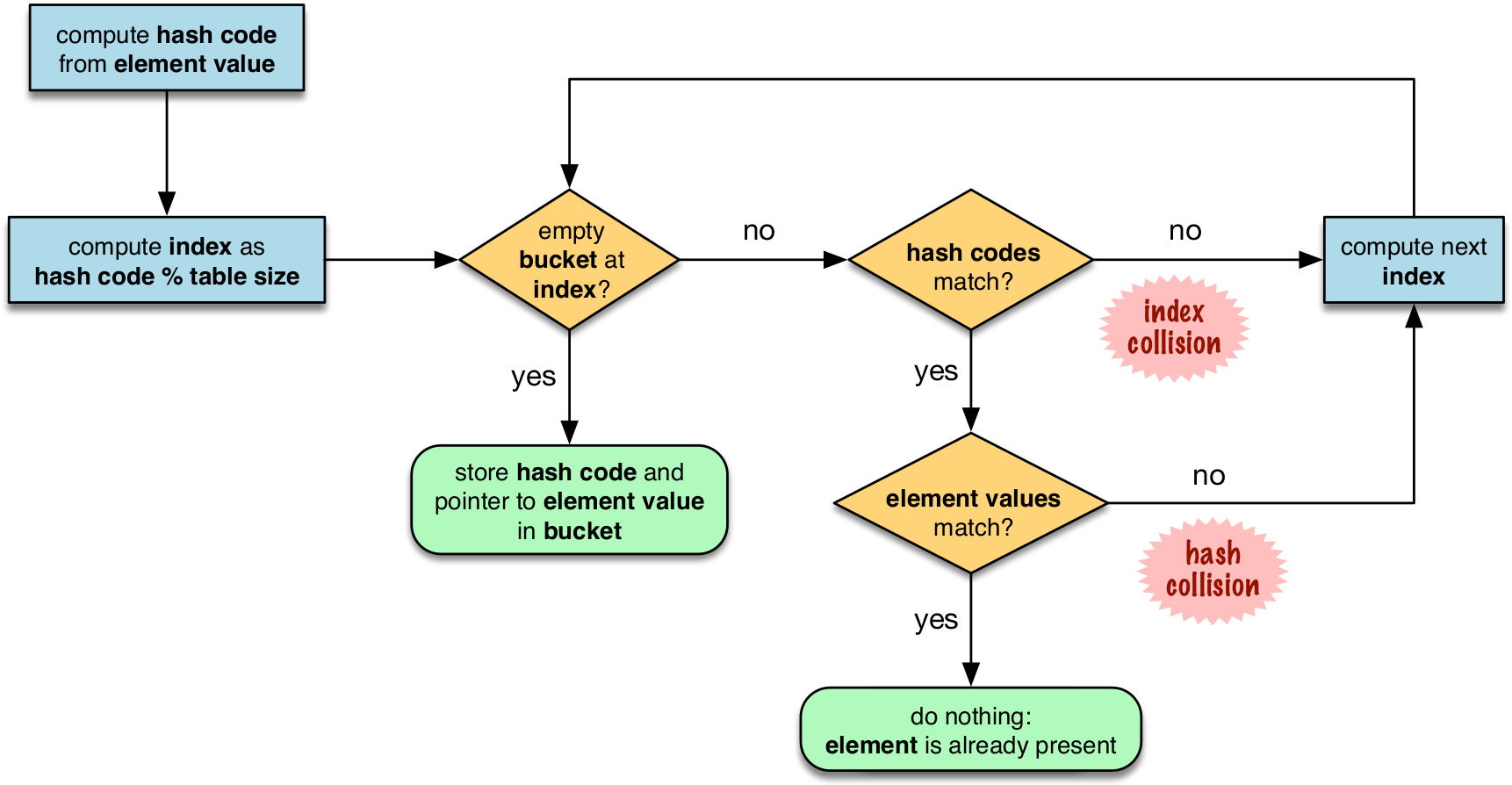

Hash Table Algo for sets

in the flowchart, notice that the first step includes the modulo operation, this is the reason why the insertion order is not preserved since the output of running the modulo on the hashvalues will not be in order, it will spread about.

on hash collisions, the probing can be done in various ways. CPython uses linear probing but also mitigates the harms of using linear probing: Incrementing the index after a collision is called linear probing. This can lead to clusters of occupied buckets, which can degrade the hash table performance, so CPython counts the number of linear probes and after a certain threshold, applies a pseudo random number generator to obtain a different index from other bits of the hash code. This optimization is particularly important in large sets.

the last step is to actually do an equality check on the value. this is why for something to be hashable, two dunder functions must be implemented:

__hash__and__eq__

Hash table usage for dicts

Dictionary implementation benefits from 2 memory optimisations. Here’s a summary of it:

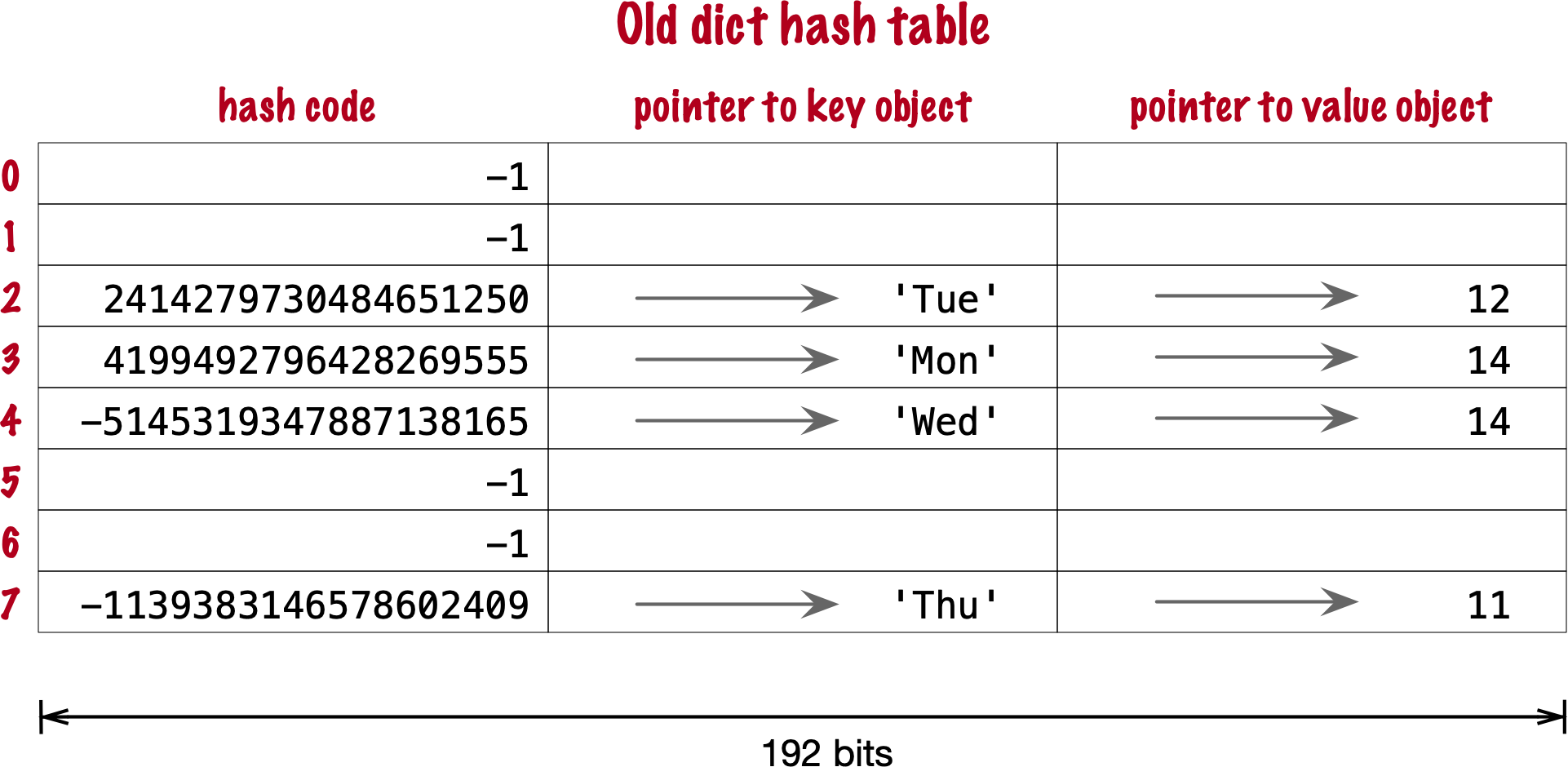

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27Here’s a summary of the **two major memory optimizations** for modern Python dictionaries, as described in the referenced Fluent Python article: 1. **Key-Sharing Dictionaries (PEP 412)** - Introduced in Python 3.3, this optimization allows multiple dictionaries that share the same set of keys (such as instance `__dict__` for objects of the same class) to share a single "keys table." - Only the values are stored separately for each dictionary; the mapping from keys to indices is shared. - This greatly reduces memory usage for objects of the same type, especially when many objects have the same attributes[1]. 2. **Compact Dictionaries** - Modern Python dictionaries use a split-table design, separating the storage of keys and values from the hash table itself. - The hash table stores indices into a compact array of keys and values, rather than storing the full key-value pairs directly in the hash table. - This reduces memory overhead, improves cache locality, and keeps insertion order predictable and efficient[1]. **In summary:** - **Key-sharing dictionaries** save memory by sharing the key structure among similar dicts. - **Compact dicts** store keys and values in separate, dense arrays, minimizing wasted space and improving performance. [1] https://www.fluentpython.com/extra/internals-of-sets-and-dicts/ [2] https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/minimizing-dictionary-memory-usage-in-python/ [3] https://python.plainenglish.io/optimizing-python-dictionaries-a-comprehensive-guide-f9b04063467a [4] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/10264874/python-reducing-memory-usage-of-dictionary [5] https://labex.io/tutorials/python-how-to-understand-python-dict-memory-scaling-450842 [6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aJpk5miPaA8 [7] https://www.reddit.com/r/pythontips/comments/149qlts/some_quick_and_useful_python_memory_optimization/ [8] https://www.tutorialspoint.com/How-to-optimize-Python-dictionary-access-code [9] https://labex.io/tutorials/python-how-to-understand-python-dictionary-sizing-435511 [10] https://www.joeltok.com/posts/2021-06-memory-dataframes-vs-json-like/ [11] https://www.linkedin.com/advice/0/what-strategies-can-you-use-optimize-python-dictionaries-fqcufOriginal implementation

- there’s 3 fields to keep, 64 bits each

- first two fields play the same role as they do in the implementation of sets. To find a key, Python computes the hash code of the key, derives an index from the key, then probes the hash table to find a bucket with a matching hash code and a matching key object. The third field provides the main feature of a dict: mapping a key to an arbitrary value

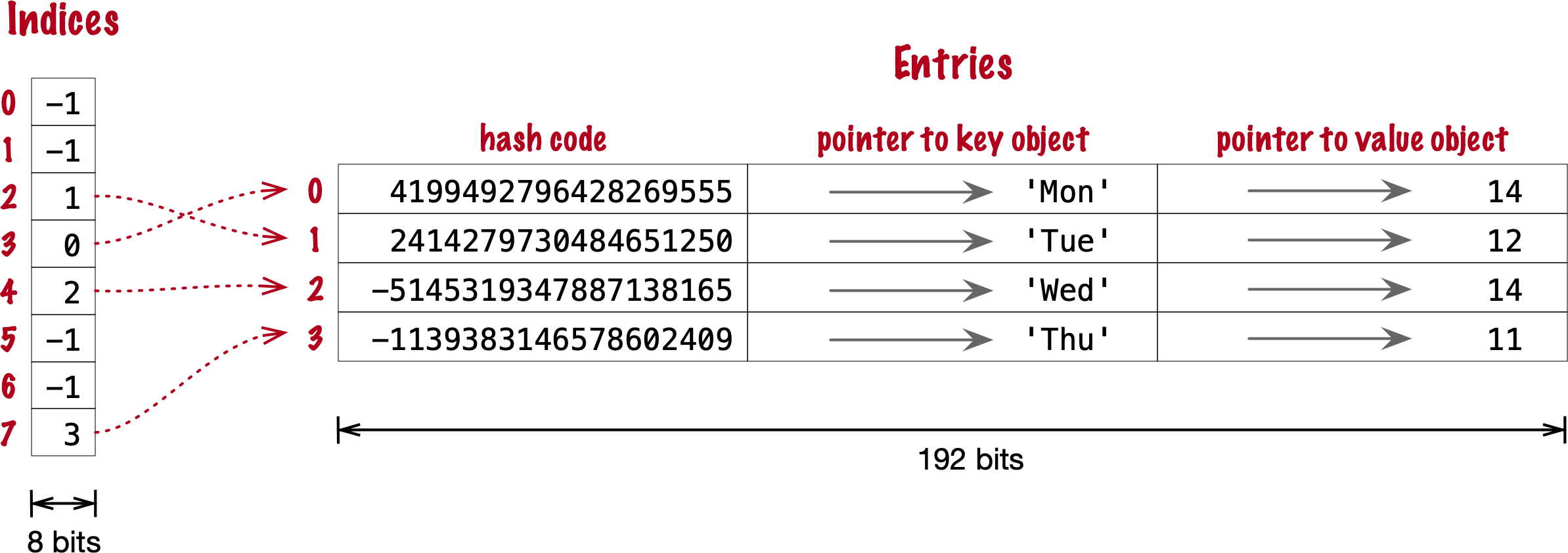

Optimisation 1: Compact implementation

- there’s an indices table extra that has a smaller width (hence compact)

- Raymond Hettinger observed that significant savings could be made if the hash code and pointers to key and value were held in an entries array with no empty rows, and the actual hash table were a sparse array with much smaller buckets holding indexes into the entries array

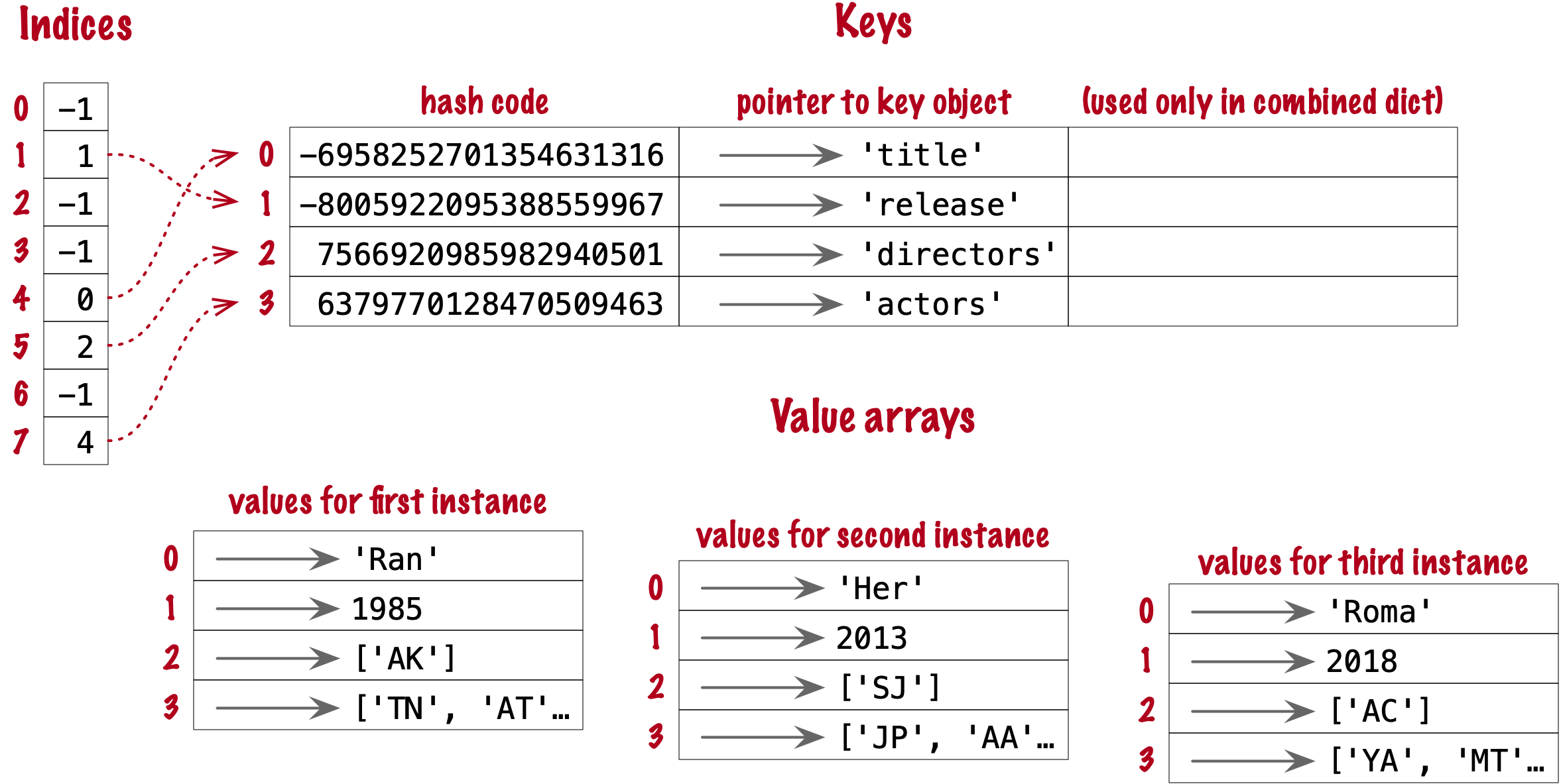

Optimisation 2: Key-Sharing Dictionary ⭐️

The combined-table layout is still the default when you create a dict using literal syntax or call

The combined-table layout is still the default when you create a dict using literal syntax or call dict(). A split-table dictionary is created to fill the__dict__special attribute of an instance, when it is the first instance of a class. The keys table is then cached in the class object. This leverages the fact that most Object Oriented Python code assigns all instance attributes in the__init__method. That first instance (and all instances after it) will hold only its own value array. If an instance gets a new attribute not found in the shared keys table, then this instance’s__dict__is converted to combined-table form. However, if this instance is the only one in its class, the__dict__is converted back to split-table, since it is assumed that further instances will have the same set of attributes and key sharing will be useful.

Practical Consequences

of how

setswork- need to implement the

__hash__and__eq__functions - efficient membership testing, the possible overheads is the small number of probing the might need to be done to find a matching element or an empty bucket

- Memory overhead:

- an array of pointers is the most compact, sets have significant memory overhead. hash table adds a hash code per entry, and at least ⅓ of empty buckets to minimize collisions

- Insertion order is somewhat preserved but it’s not reliable.

- Adding elements to a set may change the order of other elements. That’s because, as the hash table is filled, Python may need to recreate it to keep at least ⅓ of the buckets empty. When this happens, elements are reinserted and different collisions may occur.

- need to implement the

of how

dictswork- need to implement both the dunder methods

__hash__and__eq__ - key search almost as fast as element searches in sets

- Item ordering preserved in the entries table

- To save memory, avoid creating instance attributes outside of the init method. If all instance attributes are created in init, the dict of your instances will use the split-table layout, sharing the same indices and key entries array stored with the class.

- need to implement both the dunder methods

Modern dict Syntax

- dict Comprehensions

Unpacking Mappings

- we can use the unpacking operator

**when keys aer all strings - if there’s any duplicates in the keys then the later entries will overwrite the earlier ones

- we can use the unpacking operator

Merging Mappings with | (the union operator)

- there’s an inplace merge

|=and there’s a normal merge that creates a new mapping| - it’s supposed to look like the union operator and you’re doing an union on two mappings

- there’s an inplace merge

Syntax & Structure: Pattern Matching with Mappings cool

this will work with anything that is a subclass or virtual subclass of Mapping

we can use the usual tools for this:

can use partial matching

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11data = {"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3} match data: case {"a": 1}: print("Matched 'a' only") case {"a": 1, "b": 2}: print("Matched 'a' and 'b'") case _: print("No match") # in this case, the order of the cases matter, the first match is evaluatedcan capture keys using the

**restsyntax1 2 3match data: case {"a": 1, **rest}: print(f"Matched 'a', rest: {rest}")can be arbitrarily deeply nested

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21data = { "user": { "id": 42, "profile": { "name": "Alice", "address": {"city": "Wonderland"} } } } match data: case { "user": { "profile": { "address": {"city": city_name} } } }: print(f"City is {city_name}") case _: print("No match")

Keys in the pattern must be literals (not variables), but values can be any valid pattern, including captures, literals, or even further nested patterns

Pattern matching works with any mapping type (not just dict), as long as it implements the mapping protocol

- Guards (if clauses) can be used to add extra conditions to a match.

More on virtual sub-classes (and how it’s similar to mixins)

should be used when we can’t control the class (e.g. it’s an external module) but we want to adapt it

allows the indication that a class conforms to the interface of another – to adapt to multiple interfaces

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80A **virtual subclass** in Python refers to a class that is recognized as a subclass of an abstract base class (ABC) without actually inheriting from it in the traditional sense. This mechanism is provided by the `abc` module and is achieved by *registering* a class as a virtual subclass of an ABC using the `register()` method[4][5][8]. ### Core Mental Model - **Traditional subclassing**: A class (the subclass) inherits from another (the superclass), forming a direct relationship. Methods and attributes are inherited, and `issubclass()` and `isinstance()` reflect this relationship[3]. - **Virtual subclassing**: A class is *declared* to be a subclass of an ABC at runtime, without modifying its inheritance tree or MRO (Method Resolution Order). This is done by calling `ABC.register(SomeClass)`. After registration, `issubclass(SomeClass, ABC)` and `isinstance(instance, ABC)` will return `True`, but `SomeClass` does not actually inherit from `ABC`[4][5][8]. ### Why Use Virtual Subclasses? - **Third-party integration**: If you want to treat classes from external libraries as conforming to your interface (ABC), but you cannot or do not want to modify their source code to inherit from your ABC, you can register them as virtual subclasses[1][8]. - **Interface compliance**: Virtual subclassing is a way to declare that a class “conforms to” an interface, even if it doesn’t inherit from it, as long as it implements the required methods (i.e., it follows the protocol)[2][5]. - **Decoupling**: It allows you to decouple interface definition (the ABC) from implementation, enabling more flexible and extensible designs. ### Example Suppose you have an ABC and an external class: ```python from abc import ABC class Car(ABC): def drive(self): pass class Tesla: def drive(self): print("Driving in Tesla") ``` You want to use `isinstance(obj, Car)` to check if an object can be driven, but `Tesla` does not inherit from `Car`. You can register it: ```python Car.register(Tesla) print(issubclass(Tesla, Car)) # True print(isinstance(Tesla(), Car)) # True ``` Now, `Tesla` is a *virtual subclass* of `Car`, even though it doesn't inherit from it[4][5][8]. ### Key Properties - **No inheritance**: Virtual subclasses do not inherit methods or properties from the ABC. Registration only affects `issubclass()` and `isinstance()` checks[4][8]. - **No MRO change**: The ABC does not appear in the virtual subclass’s MRO, so `super()` calls and method resolution are unaffected[4]. - **Runtime declaration**: Registration can be done at runtime, providing flexibility for dynamic systems[4][5]. ### Relationship to Other Python Typing Models | Model | Relationship Mechanism | Example Use Case | |-----------------------|-------------------------------|---------------------------------------------------| | Duck typing | Implements required interface | Any object with `drive()` method can be used | | Virtual subclass | Registered with ABC | External class made compatible with ABC interface | | Classical inheritance | Inherits from superclass | Subclass extends or customizes base functionality | Virtual subclassing sits between **duck typing** (no explicit relationship, just interface compliance) and **classical inheritance** (explicit parent-child relationship), allowing you to *declare* interface compliance without direct inheritance[1][6]. ### Reference Implementation The mechanism is built into the `abc.ABCMeta` metaclass, which provides the `register()` method for this purpose[4][5]. > "You can also register unrelated concrete classes (even built-in classes) and unrelated ABCs as 'virtual subclasses' – these and their descendants will be considered subclasses of the registering ABC by the built-in function, but the registering ABC won’t show up in their MRO nor will method implementations defined by the registering ABC be callable..."[4] ### Practical Implications - **Type checks**: Enables more expressive and flexible type checks in frameworks and libraries. - **Backward compatibility**: Allows legacy or third-party classes to be integrated into new type hierarchies without code changes. - **Protocol enforcement**: Encourages protocol-oriented design in a language that is otherwise dynamically typed. In summary, a **virtual subclass** in Python is a class that, through explicit registration, is treated as a subclass of an abstract base class for type-checking purposes, without requiring direct inheritance or MRO modification[4][5][8]. This is a powerful tool for interface-oriented design and decoupled architectures. [1] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/51666120/whats-the-usage-of-a-virtual-subclass [2] https://www.reddit.com/r/learnpython/comments/9fgdib/virtual_subclasses/ [3] https://realpython.com/ref/glossary/subclass/ [4] https://docs.python.org/3/library/abc.html [5] https://www.demo2s.com/python/python-virtual-subclasses.html [6] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/51666120/whats-the-usage-of-a-virtual-subclass/51666808 [7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_class [8] https://kavianam.ir/Virtual-Subclass-in-Python [9] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/57602862/what-is-indirect-and-virtual-subclass [10] https://hynek.me/articles/python-subclassing-redux/- a virtual subclass should be seen more like a mixin rather than multiple inheritance

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54**Virtual subclassing** in Python is *not* the canonical or idiomatic mechanism for achieving "multiple extends" (i.e., multiple inheritance) or adapting to multiple interfaces in the way you might do in statically-typed languages like Java or C#. Instead, Python supports **multiple inheritance** natively and directly through its class definition syntax, and this is the primary mechanism for a class to inherit from multiple parents and thus "implement multiple interfaces"[1][5][6]. ### Multiple Inheritance: The Pythonic Way Python allows a class to inherit from any number of parent classes simply by listing them in the class definition: ```python class MyClass(InterfaceA, InterfaceB, SomeBase): pass ``` This means `MyClass` will inherit all methods and attributes from `InterfaceA`, `InterfaceB`, and `SomeBase`, and will be considered a subclass of each for purposes of `issubclass()` and `isinstance()` checks[1][5][6]. This is the direct and idiomatic way to "extend" multiple interfaces or base classes in Python, and is how you would typically express that a class conforms to multiple protocols or contracts. ### Virtual Subclassing: Purpose and Limitations **Virtual subclassing** via `ABC.register(SomeClass)` is a mechanism for declaring that a class should be *recognized* as a subclass of an abstract base class (ABC) for the purposes of type checking, without actually inheriting from it. This is especially useful when you want to adapt a class (often from a third-party library) to an interface you control, but cannot or do not want to modify its source code[7]. - **Virtual subclassing does not provide code sharing**: The registered class does not inherit any methods or properties from the ABC; it is only recognized as a subclass for `issubclass()` and `isinstance()` checks. - **No method resolution order (MRO) change**: The ABC does not appear in the registered class's MRO, so method resolution and `super()` calls are unaffected. - **No attribute/method adaptation**: If the registered class does not implement the required methods, you get runtime errors. ### Adapting to Multiple Interfaces If you want a class to *adapt* to multiple interfaces: - **If you control the class**: Use multiple inheritance directly. This is idiomatic and gives you both interface conformance and code sharing[1][5][6]. - **If you do not control the class**: Use virtual subclassing to declare interface conformance, but be aware this is only for type checks and does not provide actual method implementations[7]. ### Mixin Pattern A related idiom is the **mixin**: a class designed to be used as a base class that provides additional methods, typically without defining its own state. Mixins are commonly used in Python to modularly add functionality via multiple inheritance, and are a way to "compose" behaviors without the pitfalls of deep inheritance hierarchies[6]. ### Summary Table | Mechanism | Code Sharing | Interface Conformance | Idiomatic Use | |---------------------|-------------|----------------------|----------------------| | Multiple Inheritance| Yes | Yes | Implementing multiple interfaces, mixins | | Virtual Subclassing | No | Yes (type checks) | Adapting foreign classes to your ABCs | **In summary:** Python's primary and idiomatic way to "extend" multiple interfaces is through direct multiple inheritance. **Virtual subclassing** is a supplementary mechanism for adapting existing classes to an interface for type checks, but it does not provide code sharing or actual interface adaptation[1][5][6][7]. [1] https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/understanding-class-inheritance-in-python-3 [2] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/66849568/issubclass-and-multiple-inheritance [3] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/27545888/is-multiple-inheritance-from-the-same-base-class-via-different-parent-classes-re [4] https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/291061/is-there-a-better-pattern-than-multiple-inheritance-here [5] https://dataplatform.cloud.ibm.com/docs/content/wsd/nodes/scripting_guide/clementine/jython/clementine/python_inheritance.html?audience=wdp&context=dph&context=analytics&context=analytics&context=analytics&context=analytics&context=analytics&context=analytics&context=cpdaas [6] https://openstax.org/books/introduction-python-programming/pages/13-5-multiple-inheritance-and-mixin-classes [7] https://hynek.me/articles/python-subclassing-redux/ [8] https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/classes.html [9] https://realpython.com/inheritance-composition-python/ [10] https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/multiple-inheritance-in-python/

Standard API of Mapping Types

The recommendation is to wrap a dict by composition instead of subclassing the Collection, Mapping, MutableMapping ABCs.

Note that because everything ultimately relies on the hastable, the keys must be hashable (doesn’t matter if the value is hashable)

What Is Hashable

- ✅ User Defined Types:

for user defined types, the hashcode is the

id()of the object and the__eq__method from theobjectparent class compares the object ids.

gotcha: there’s a salt applied to hashing

And the salt differs across python processes.

The hash code of an object may be different depending on the version of Python, the machine architecture, and because of a salt added to the hash computation for secu‐ rity reasons.3 The hash code of a correctly implemented object is guaranteed to be constant only within one Python process.

- ✅ User Defined Types:

for user defined types, the hashcode is the

Overview of Common Mapping Methods: using

dict,defaultdictandOrderedDict:NOTER_PAGE: (115 . 0.580146)

Inserting or Updating Mutable Values: when to use setdefault

Should use setdefault when you want to mutate the mapping and there’s nothing there

E.g. you wanna fill in empty default values

so instead of doing this which has 2 searches through the dict index ⛔️

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18import re import sys WORD_RE = re.compile(r'\w+') index = {} with open(sys.argv[1], encoding='utf-8') as fp: for line_no, line in enumerate(fp, 1): for match in WORD_RE.finditer(line): word = match.group() column_no = match.start() + 1 location = (line_no, column_no) # this is ugly; coded like this to make a point occurrences = index.get(word, []) occurrences.append(location) index[word] = occurrences # display in alphabetical order for word in sorted(index, key=str.upper): print(word, index[word])we could do just do a single search within the dict index and do:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15"""Build an index mapping word -> list of occurrences""" import re import sys WORD_RE = re.compile(r'\w+') index = {} with open(sys.argv[1], encoding='utf-8') as fp: for line_no, line in enumerate(fp, 1): for match in WORD_RE.finditer(line): word = match.group() column_no = match.start() + 1 location = (line_no, column_no) index.setdefault(word, []).append(location) # display in alphabetical order for word in sorted(index, key=str.upper): print(word, index[word])setdefault returns the value, so it can be updated without requiring a second search.

Automatic Handling of Missing Keys

We have 2 options here.

defaultdict: Another Take on Missing Keys

- it’s actually a callable that we are passing as an arg, so when we do things like

boolorlistwe’re actually passing in the constructor to these builtins. - callable is stored within the

default_factoryand we can replace the factory as we wish! - interesting: if we do a membership check on a key that doesn’t exist, the default factory won’t be called yet.

- it’s actually a callable that we are passing as an arg, so when we do things like

The missing Method

:PROPERTIES: :NOTER_PAGE: (121 . 0.519175)

TLDR: subclass

UserDictinstaed ofdictto avoid these issuesTake note of the nuances in the implementation that is shown because they avoid infinite recursion.

It’s important to think of how the method delegation may introduce chances of infinite recursion.

Also, same thing for what the fallback methods are for builtin methods.

note:

k in my_dictfaster thank in my_dict.keys()Also technically

k in my_dictis faster than using thek in my_dict.keys()because it avoids the attribute lookup to find the.keysmethod.

Inconsistent Usage of missing in the Standard Library

TLDR: subclass

UserDictinstaed ofdictto avoid these issues subclassing builtin types is tricky! (will come up later in the book).Basically, this dunder method is inconsistently used. Be careful if you wanna subclass this, it may result in infinite recursions.

Variations of dict

collections.OrderedDict

Mostly the modern implementation for

dictis good enough- has some minor differences from the modern implementation of

dict:- can handle frequent reordering ops better than

dict=> useful to track recent accesses like in an LRU cache.

- can handle frequent reordering ops better than

- use it for simple implementations of an LRU cache.

- has some minor differences from the modern implementation of

collections.ChainMap

- chains together multiple mappings by holding references to the mappings

- any mods happen to the first-inserted mapping

- it’s useful to search hierarchically (search from d1, then d2, then d3) and prioritises the results found in the earlier implementation.

collections.Counter

- counters are great!!!

- GOTCHA: when things are tied, only one is returned.

example if counter looks like this:

Counter({'a': 10, 'z': 3, 'b': 2, 'r': 2, 'c': 1, 'd': 1})then if we doct.most_common(3)then even if both b and c are tied, we only get b in the result. Here’s some more context on this:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61The behavior you’re observing with `Counter.most_common(n)`—where only one of the tied elements is included when there’s a tie at the cutoff—is by design, and it’s important to understand the underlying mechanics and implications. ### Why does this happen? - **`most_common(n)` returns exactly `n` items**: The method returns the *first* `n` elements from the sorted list of items, sorted by count (descending). If multiple elements have the same count at the cutoff position, only those that appear first (according to the internal order, which is typically insertion order for equal counts) are included[1][2][9]. - **Ties are not expanded**: If two or more elements are tied for the last spot in the top `n`, only as many as needed to reach `n` are returned. The method does not automatically include all items with the same count as the nth item[6]. #### Example: ```python from collections import Counter ct = Counter({'a': 10, 'z': 3, 'b': 2, 'r': 2, 'c': 1, 'd': 1}) print(ct.most_common(3)) # Output might be: [('a', 10), ('z', 3), ('b', 2)] ``` Even though both `'b'` and `'r'` have a count of `2`, only `'b'` is included because you asked for the top 3, and `'b'` appears before `'r'` in the internal ordering[2][6]. ### How is the order determined for ties? - **Insertion order**: For elements with equal counts, their order in the result is based on the order they were first encountered in the input (Python 3.7+ dictionaries preserve insertion order)[2][9]. - **No guarantee for all ties**: There is no built-in mechanism to include all elements with the same count as the nth element unless you implement it yourself[6]. ### What if you want all tied elements included? You need to post-process the result. For example, you can: 1. Get the count of the nth item. 2. Iterate through all items and include those with counts >= nth count. ```python from collections import Counter ct = Counter({'a': 10, 'z': 3, 'b': 2, 'r': 2, 'c': 1, 'd': 1}) n = 3 top_n = ct.most_common(n) cutoff = top_n[-1][1] all_tied = [(k, v) for k, v in ct.items() if v >= cutoff] print(all_tied) ``` This will include all items with counts equal to or greater than the nth most common, including ties[6]. ### Summary - `most_common(n)` returns exactly `n` elements, even if there are ties at the last position. - For ties, only the first encountered elements (in insertion order) are included. - To include all tied elements, you must filter manually after getting the cutoff value[2][6][9]. This behavior is documented and is a common source of confusion—your observation is correct and is a subtle but important aspect of using `Counter.most_common()` in Python. [1] https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python/python-most_common-function/ [2] https://docs.python.org/3/library/collections.html [3] https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/python-counter-python-collections-counter [4] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/29240807/python-collections-counter-most-common-complexity [5] https://blog.csdn.net/weixin_43056275/article/details/124384145 [6] https://stackoverflow.com/questions/33791057/counter-most-common-is-a-little-misleading/33791292 [7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqACZvcsNug [8] https://dev.to/atqed/you-can-be-happy-to-know-python-counter-how-to-get-the-most-common-elements-in-a-list-o1m [9] https://ioflood.com/blog/python-counter-quick-reference-guide/ [10] https://dev.to/kathanvakharia/python-collections-module-counter-2gn

shelve.Shelf

- shelves are for storing pickle jars

- shelves are persistent storage for a mapping of strings to pickle objects

- A Shelf instance is a context manager, so you can use a with block to make sure it is closed after use.

Ref “Pickle’s nine flaws”

And here’s a bot summary of it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43Here is a summary of the nine flaws of Python's `pickle` module as detailed by Ned Batchelder[1][2]: 1. **Insecure** Pickle is fundamentally unsafe for untrusted data. Maliciously crafted pickles can execute arbitrary code during unpickling, as the process can invoke any callable in the Python environment—not just constructors for your objects. 2. **Old pickles look like old code** Pickle stores the exact structure of objects as they existed when pickled. If your code changes (e.g., you add or remove attributes), unpickling old data can result in objects that don't match your current codebase, leading to bugs and inconsistencies. 3. **Implicit** The serialization process is implicit and automatic: you cannot explicitly control how objects are serialized. For example, you cannot choose to serialize a datetime as an ISO8601 string instead of a datetime object. 4. **Over-serializes** Pickle serializes everything in your objects, including data you may not want to persist (like caches or open file handles). There is no straightforward way to exclude unwanted attributes, and if an attribute is not pickle-able, you'll get an exception[2]. 5. **`__init__` isn’t called** When unpickling, the `__init__` method of your class is not invoked. This can leave objects in an inconsistent state, especially if `__init__` does essential setup or side effects. 6. **Python only** Pickle is Python-specific. While there are rare cross-language implementations, they're limited and not practical for general use. This makes pickled data hard to share with non-Python systems. 7. **Unreadable** Pickles are binary blobs, not human-readable. You can't inspect or search them with standard tools, making debugging and data recovery more difficult. 8. **Appears to pickle code** Pickle will serialize references to functions and classes, but not their code—only their names. This can give the false impression that code is being serialized, but on unpickling, the code must already exist in the environment. 9. **Slow** Pickle is slower than many alternative serialization formats, both in terms of speed and efficiency. > Some of these issues can be mitigated with custom methods like `__getstate__` or `__reduce__`, but at that point, alternative serialization formats (e.g., JSON, protocol buffers) may be more robust and maintainable[1]. These flaws highlight why `pickle` is best reserved for trusted, Python-only, and short-lived data interchange scenarios—not for general-purpose or cross-system serialization. [1] https://nedbatchelder.com/blog/202006/pickles_nine_flaws.html [2] https://nedbatchelder.com/blog/tag/python.html [3] https://www.python4data.science/en/latest/data-processing/serialisation-formats/pickle/index.html [4] https://pycoders.com/issues/426 [5] https://stanforddaily.com/2019/10/11/face-it-pickles-are-bad-an-irrefutable-proof/ [6] https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/pickle-and-pickle-product-problems [7] https://diff.blog/post/pickles-nine-flaws-49891/ [8] https://pythonbytes.fm/episodes/show/193/break-out-the-django-testing-toolbox [9] https://www.reddit.com/r/Python/comments/1c5l9px/big_o_cheat_sheet_the_time_complexities_of/ [10] https://podscripts.co/podcasts/python-bytes/189-what-does-strstrip-do-are-you-sure

Subclassing UserDict Instead of dict

- key idea here is that it uses composition and keeps an internal dict within the

dataattribute - implementing other functions as we extend it will require us to use the

self.dataattribute.

- key idea here is that it uses composition and keeps an internal dict within the

Immutable Mappings

we can use a read-only

MappingProxyTypefrom thetypesmodule to expose a readonly proxythe constructor in a concrete Board subclass would fill a private mapping with the pin objects, and expose it to clients of the API via a public .pins attribute implemented as a mappingproxy. That way the clients would not be able to add, remove, or change pins by accident.

Dictionary Views

- the views are supposed to be proxies as well so they are updated. Any changes to the original mapping will be viewable as well

- because they are not sequences (they are view objects) they are not subscript-able. so doing something like

myvals[0]won’t work. If we wish, we could convert it to a list, but then it’s a copy, it’s no longer a live dynamic read-only proxy.

Practical Consequences of How dict Works

why we should NOT add instance attrs outside of

__init__functionsThat last tip about instance attributes comes from the fact that Python’s default behavior is to store instance attributes in a special dict attribute, which is a dict attached to each instance.9 Since PEP 412—Key-Sharing Dictionary was implemented in Python 3.3, instances of a class can share a common hash table, stored with the class. That common hash table is shared by the dict of each new instance that has the same attributes names as the first instance of that class when init returns. Each instance dict can then hold only its own attribute values as a simple array of pointers. Adding an instance attribute after init forces Python to create a new hash table just for the dict of that one instance

also KIV the implementation of

__slots__and how that is even better of an optimisation.

Set Theory

As we had found out from the extension writeup, the intersection operator is a great oneliner found = len(needles & haystack) or found = len(set(needles) & set(haystack)) to be more generalisable (though there’s the overhead from building the set)

Set Literals

- using the set literal (

{1,2,3}) for construction is faster than using the constructor (set([ 1,2,3 ])) because the constructor will have to do a key lookup to fetch the function - the literal directly uses a

BUILDSETbytecode

- using the set literal (

Set Comprehensions

- looks almost the same as dictcomps

Practical Consequences of How Sets Work

- Set Operations

Set Operations on dict Views

.keys()and.items()are similar to frozenset.values()may work like this too but only if all the values in the dict are hashable

Even better: the set operators in dictionary views are compatible with set instances.

Chapter Summary

Further Reading

Chapter 4. Unicode Text Versus Bytes

What’s New in This Chapter

Character Issues

- “string as a sequence of characters” needs the term “character” to be defined well

- in python 3, it’s “unicode

- Unicode char separates:

- identity of the char => refers to its code point

- the byte representation for the char => dependent on the encoding used (codec between code points and byte sequences)

Byte Essentials

- binary sequences, there are 2 builtin types:

- mutable:

bytearray - immutable:

byte

- mutable:

- Each item in bytes or bytearray is an integer from 0 to 255

- literal notation depends (just a visual representation thing):

- if in ascii range, display in ascii

- if it’s a special char like tab and such, then escape it

- if amidst apostrophes, then use escape chars

- else just use the hex notation for it e.g.

\x100

- most functions work the same, except those that do formatting and those that depend on unicode data so won’t work:

- case, fold

- regexes work the same only if regex is compiled from a binary sequence instead of a

str - how to build

bytesorbytearray:- use

bytes.fromhex() - use bytes.encode(“mystr”, encoding=“utf-8”)

- use soemthing that implements buffer protocol to create from source object to new binary sequence (e.g.

memoryview).- This needs us to explicitly typecast